Classic novels have some surprising things in common with celebrity scandals. Adultery is common in both, and both have a tendency to dissolve into the general culture; you can absorb plenty of information about them without trying to. I have no interest in Brad Pitt and Jennifer Aniston, and I've never read a magazine article or watched a television program about their relationship, yet somehow I know an awful lot about it. So it is with Leo Tolstoy's "Anna Karenina," a novel I've never read, but whose plot and characters seem quite familiar, especially now that "Anna Karenina" has been enthusiastically recommended to the general public by such luminaries as Candace Bushnell and Oprah Winfrey. It is widely lauded as the Tolstoy book to read; as pinot noir is to California wine, so "Anna Karenina" is to fat Russian novels.

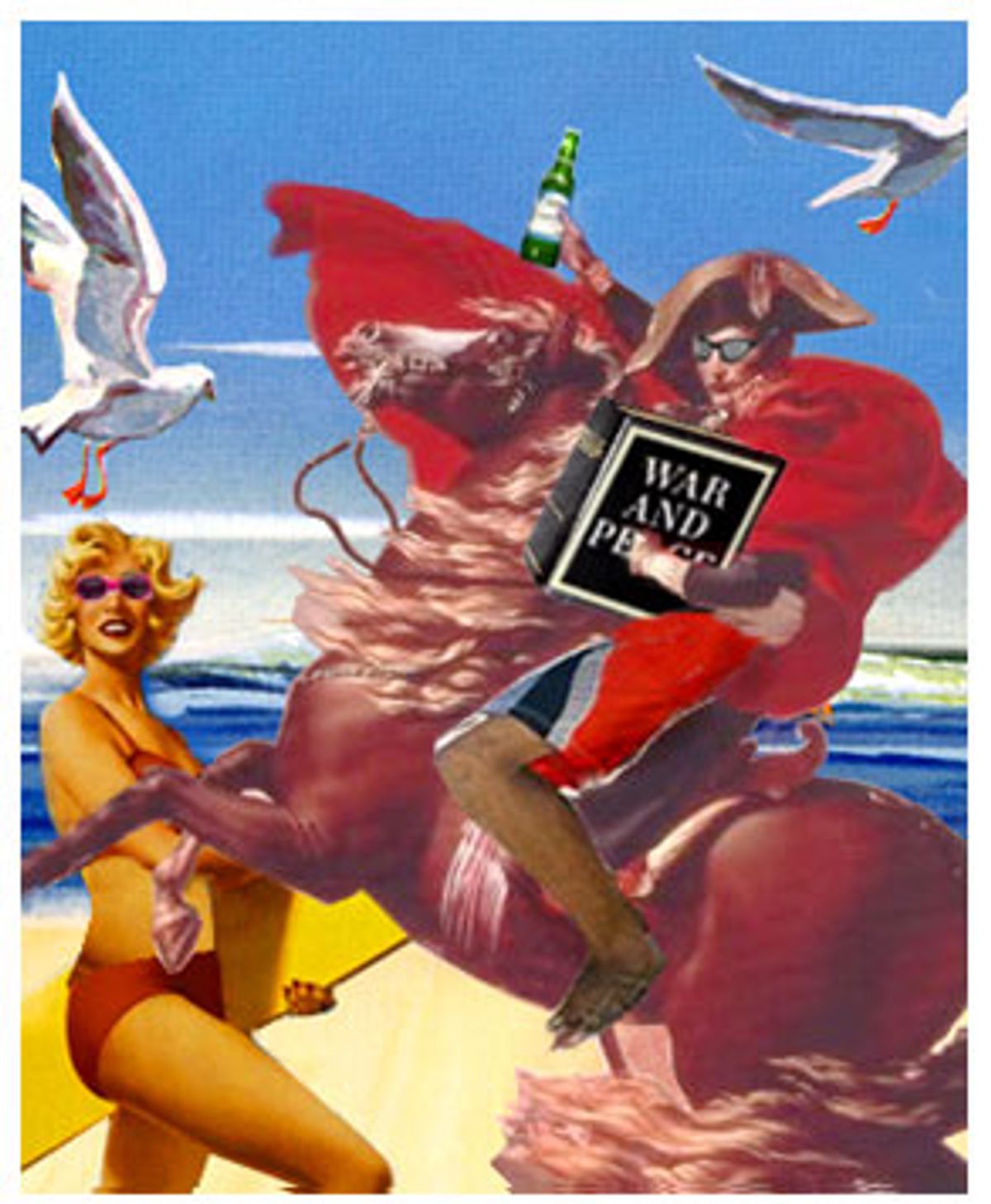

"War and Peace" is another matter. What can you pick up about Tolstoy's earlier and more massive novel if you haven't read it? That there are characters named Boris and Natasha, that it's set during the Napoleonic Wars, that Napoleon himself appears as a character (and not, they say, a very interesting one). Slim pickings for a book that's described on the back cover of my Signet Classic paperback edition as "probably the greatest novel ever written."

I chose "War and Peace" for my Summer School assignment because my friend Sallie had given me the idea that -- contrary to its reputation as the quintessential unfinished summertime reading project -- the novel was something of an old-fashioned page turner, like "Our Mutual Friend." This is not, strictly speaking, true. There are several long, detailed battle scenes and frequent expository interludes -- essays on military strategy, history and the nature of free will -- that make for some pretty heavy sledding. Instead, this is a book that, like a capricious wind with a sailboat, picks you up and sends you scudding along at an exhilarating clip then suddenly subsides into a lull.

There's not a lot of common knowledge about "War and Peace" kicking around partly because the book is so dauntingly long, but mostly because it's so hard to say what it's about. There's no central character, and no main story line. The novel is like one of those vast, complicated paintings in which no single figure or group of figures dominates the whole, but if you let your eye wander over the surface, you find dozens of moments and portraits, each sad or horrible or funny enough to be the subject of a picture all on its own. You can't really wander through a novel, though, and at first what feels like a lack of focus can be frustrating, as Tolstoy pops in on various characters and subplots like one of his Petersburg society women out for an afternoon of visits.

Soon, though, it becomes impossible to resist "War and Peace," and its author takes on a God-like aspect. There's an Olympian neutrality to the way Tolstoy regards his characters; he sees their most intimate thoughts but doesn't judge them. In the best 19th century third-person narrator tradition, he feels free to tell rather than show you what these people are like, yet somehow leaves you free to draw your own conclusions about them. Soon enough, you'll have to revise your opinion.

At first, the saturnine Prince Andrei is simply one of those men who consider themselves superior to everyone around them -- and he has a point. We meet him, as the novel opens, in 1805, at a high-society "soirie" where the guests, including Andrei's wife, Lisa, behave with an oppressive, vapid artificiality. (One nobleman dispenses compliments "like a wound-up clock, saying by force of habit things he did not even expect to be believed.") Perhaps Andrei is right to sneer and yawn at this crowd, and to regard his marriage as a mistake and a burden. (At one point, he's disgusted to overhear his wife repeating the same "amusing" piece of gossip for the sixth time.) But later in the novel, in a disorienting shift, both Prince Andrei and the reader are obliged to acknowledge the limits of Andrei's own judgment, and Lisa is cast in a different light.

Each of the novel's aristocratic main characters possesses qualities that make for an appealing contrast to that Petersburg party in the first chapter: Prince Andrei's intellectual and spiritual discrimination; the searching idealism of young Pierre; the unstudied, joyful vivacity of Natasha, who is still a child when the book begins. Those same qualities become alternately charming, irksome and dangerous as the circumstances change. Andrei slips into despair when he encounters the horrors and idiocy of war. Pierre falls for a series of ridiculous "answers," ranging from Freemasonry to numerology. Natasha's impetuous heart leads her into the clutches of a rake.

The long view Tolstoy takes of these people and their fates naturally fosters a sense of irony. What surprised me most about "War and Peace" is how funny it can be. Here Prince Andrei contemplates the ways different Europeans maintain their military confidence:

"Only a German bases his self-assurance on an abstract idea: science, that is, the supposed knowledge of absolute truth. A Frenchman's self-assurance stems from his belief that he is mentally and physically irresistibly fascinating to both men and women. An Englishman's self-assurance is founded on his being a citizen of the best organized state in the world and on the fact that, as an Englishman, he always knows what to do, and that whatever he does as an Englishman is unquestionably correct. An Italian is self-assured because he is excitable and easily forgets himself and others. A Russian is self-assured simply because he knows nothing and does not want to know anything, since he does not believe in the possibility of knowing anything fully."

This humor, however, is fond rather than scalding. Tolstoy treats each of his characters -- as well as the dozens of minor figures throughout the book -- with equal portions of sympathy. Like a good father, he loved them all, I suppose, even Natasha's rake, who comes off as feckless rather than malevolent. Perhaps most astonishing to me was Tolstoy's ability to make me love Prince Andrei's sister, Marya, a pious, long-suffering girl much like Jane Austen's priggish Fanny Price (from "Mansfield Park") and yet somehow, miraculously, touching rather than irritating. (And, oh, how distressing when Marya and Natasha first meet and hate each other on sight!)

To describe Tolstoy as majestically fair probably sounds like faint praise in an age that admires passionate partiality. In fact, Tolstoy's impartiality is liberating. In the fictional passages of "War and Peace" (as opposed to the mini-lectures the count decides to deliver now and then), you rarely feel the author at your elbow, telling you what to think or whom to root for. Everything interests him and everyone has a point of view that merits consideration. In a way, Tolstoy is the embodiment of the kind of novelist that, in our time, Tom Wolfe has called for but can never hope to really be, the writer who uses a journalist's skills to show us the world.

I'm told that the classic Russian novel is not even really a novel at all, but a conglomeration of literary modes designed to fill enormous books to be read by people who had few other diversions. So there's a bit of philosophizing and ample servings of history running alongside the story of who-will-Natasha-marry. There are also scenes of city and army life with the quality of memoir, or dispatches from the front. These can be spectacularly immediate, abrupt plunges into the moment. You are there, at the burning of Smolensk:

"At one moment the flames died down and were lost in the black smoke, then suddenly flared up again, illuminating with fantastic clarity the faces of the people crowded at the crossroads. Black figures were flitting about before the fire, and talking and shouting could be heard above the incessant crackling of the blaze."

Or, in a more homely and nostalgic vein, with Natasha and her young relatives at Christmas, racing through the snowy wood in sledges to a neighbor's house for an impromptu performance in mummers costumes:

"The horses kicked up the fine, dry snow into the faces of those in the sledge; there was a jingling of bells beside them and they caught confused glimpses of swiftly moving legs and the shadow of the troika they were passing. From various directions came the whistling of runners over snow and the screams of girls."

"War and Peace" isn't about burning towns or sledge rides but while you're reading these and many other passages, they seem to be the reason why the book exists. While each scene Tolstoy describes is on the page, it is the center, the occasion for which he has collected us together to read this tale, until the next one comes along and it in turn wins the same loving and scrupulous attention. For this is just how the events Tolstoy describes completely fill the minds and hearts of the people who are experiencing them and seem to be what their lives are about at each particular, irreplaceable moment. I've always wondered why people say that "War and Peace" is more like life itself than a novel, and now I know.

Shares